This article was originally published in The Impact.

It’s easy to understand why large corporations partner with innovative climatetech startups. As the climate transition gains momentum, established players in industries from energy to CPG recognize that collaborating with external innovators is essential to meeting their sustainability goals. More than that, in any rapidly changing space, innovation is a matter of survival – disrupt or be disrupted – and in the climatetech space, corporations understand that most of the industry’s disruptive potential comes from startups.

It might be slightly less obvious why startups seek corporate partners. But for startups in general, and climatetech startups in particular, corporations unlock key commercialization pathways.

First and foremost, most climatetech startups operate in B2B spaces. Corporations, therefore, often serve as important customers, or channels to customers, for startups. Second, corporations have the specialized resources and financial scale that can help capital-intensive climatetech companies succeed – from financial capital to specialized research facilities. Finally, with their global footprints and wide-reaching market access, multinational corporations can be a springboard for worldwide deployment.

But startups fear wasting time

Startups are sometimes reluctant to pursue corporate partnerships. Corporations can be opaque and complex. Their decision-making processes are quite slow when measured on startup timescales. Startups fear that partnership discussions will bog them down without producing results.

It’s true that without a clear sense of direction, startup-corporate partnerships can falter. It’s helpful, therefore, to have a structure in mind when navigating these relationships.

Navigating three phases of partnership development

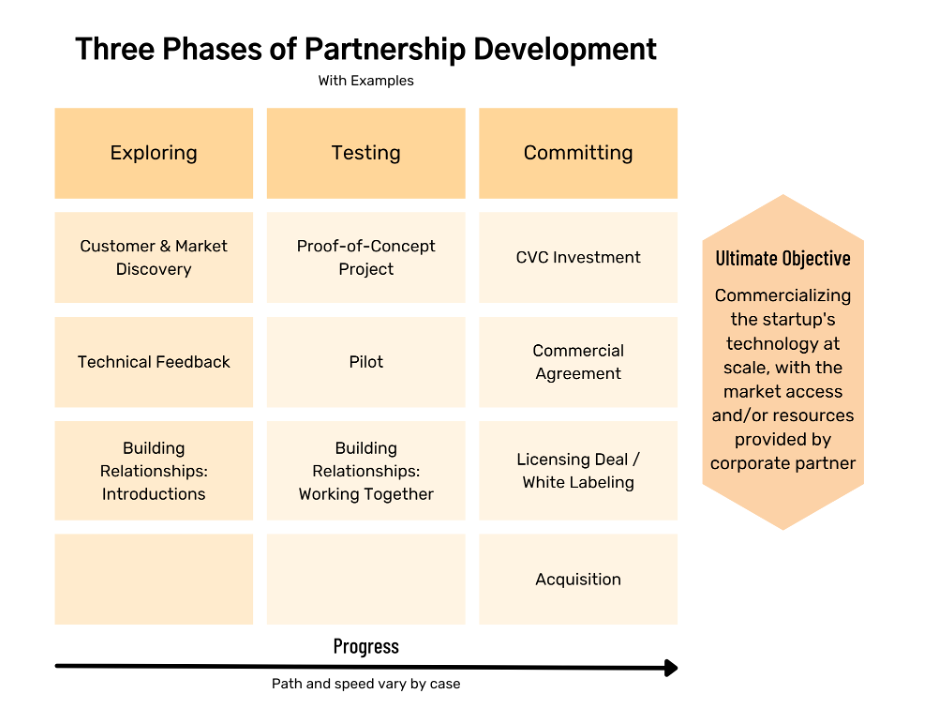

Broadly speaking, all partnership activity has the same end goal: commercializing the startup’s technology at scale because of the market access and/or resources provided by the corporation. Startups can therefore envision the partnership trajectory as having three main phases toward this goal: exploration, testing, and commitment.

The partnership trajectory begins with exploration.

In the exploration phase, startups and corporate partners learn about each other and evaluate their long-term relationship potential. The exploration phase can be beneficial for startups in and of itself. During exploration, startups can ask corporations to provide insight into target markets and help with customer discovery.

For their part, corporations usually want to evaluate a startup’s technology during exploration. Startups may receive helpful technical feedback as a result of these discussions. It’s a good idea to have NDAs in place for exploratory partnerships, and to exclude the possibility of joint IP creation until later in the partnership trajectory. Startups can rest assured that corporations usually want NDA protection just as much as startups do.

Not to be overlooked, one of the most important outcomes of the exploration phase is simple trust-building.

If exploration goes well, the next ze step in the partnership trajectory is testing. Proof-of-concept projects (little tests) and pilots (big tests) are two common testing formats.

In the testing phase, a hypothesis is formulated and results are generated. The hypothesis may seek to demonstrate performance levels for the startup technology or test the startup technology’s compatibility with the corporation’s technology, for example.

As opposed to the exploration phase, a testing phase has a defined timeline, objective, and, most importantly, clear next steps that are unlocked based on the results of the test. A critical function of the testing phase is that it secures the corporation’s attention for the duration of the test and builds a bridge to long-term commitment.

As during the exploration phase, relationships continue to be evaluated and strengthened during the testing phase.

The final phase of the partnership trajectory is commitment.

In the commitment phase, formal partnerships materialize in a variety of forms, from CVC investments, to commercial agreements, to licensing deals, to acquisitions, and more.

Often, rather than an ending, these partnerships signify the true beginning of a startup and corporation’s joint efforts toward commercializing the startup’s technology at scale. What makes the commitment phase significant is the fact that both parties have put capital – financial, reputational, or both – on the line to achieve shared success.

While the evaluation and testing phases of the partnership trajectory have standalone benefits for startups, commitment partnerships are the ultimate prize of partnership activities. They represent the startup and corporate working together in an enduring way to commercialize the startup’s technology at scale.

Is it always so cut-and-dry?

Absolutely not! The path from exploration to testing to commitment is sometimes nonlinear. Some partnerships develop quickly; others (many) progress more slowly.

Some partnerships focus on technological or market synergies alone, while others seek pure financial investment. More commonly, however, I see two or three of these activities pursued in parallel, as startups and corporations seek to evaluate strategic alignment across multiple axes.

The world of climatetech startup-corporate partnerships has never been more dynamic or exciting. With this simple framework in mind, startups can organize their efforts and increase the odds that the time they invest in pursuing corporate partnerships yields meaningful results.